Tracing the Quiet Revolt of Léon Spilliaert

A Modernist in Symbolist Disguise

Rejecting art school early on and refusing to use oil paint - essential for commercial success - Spilliaert pursued his art independently, exploring the darkest shades of India ink, watercolour, pencil, and gouache. His work forms a remarkably consistent whole, leaving a coherent, almost hypnotic impression on first encounter. The repetition of deserted seashores and empty streets borders on obsession. We begin to wonder: are we looking at a city, or entering the artist’s own state of mind?

“School, teachers, academy, anything to do with it all horrified me.”

“At school they stole my soul, and I never got it back. Hours and hours I spent there, what a waste of time. I preferred drawing in my sketchbooks.” - Spilliaert

Rejecting art school early on and refusing to use oil paint (essential for commercial success), Spilliaert explored his art independently, relishing in all the dark shades of India ink wash, watercolour, pencil, and gouache. There is a remarkable consistency to his body of work, and it makes a very coherent impression on one’s first encounter. His repetitive depiction of deserted seashores and empty streets verges on obsession. We begin to wonder - are we looking at the city as a geographical location, or are we entering the artist’s state of mind?

Spilliaert was born in 1881 in Ostend, Belgium. A child prodigy and son of a perfume shop owner, Spilliaert drew from an early age. An autodidact, he turned into an outstanding draughtsman and a voracious reader. A member of cabinets de lecture - fashionable reading places for bookworms at the turn of the century Brussels - Spilliaert was friends with famous Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig and Emilie Verhaeren, an important Belgian Symbolist poet (whose book he later illustrated). The best such salon belonged to a publisher Edmond Deman, who was known for his luxuriously designed editions of the most in-vogue authors of the day. Spilliaert, the bibliophile, met Deman and was engaged to illustrate quite a few editions for Demon, including Maeterlinck’s book of symbolist poetry - Les Serres Chaudes (Hothouse) and sketches inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s Fall of The House of Usher. Although his illustrations were in demand and his entire body of work exhibits literary sensibility, Spilliaert later confessed in a postcard to Deman: “I am not good at interpreting other people’s dreams; I have too many of my own.”

Spilliaert remained highly independent and humble, never considering himself to be a genius. Often compared to Munch (hypnotic gaze in portraits), Hammershøi (sparse interiors), and even de Chirico (surreal use of space), he was categorised as a Symbolist with a touch of mysticism. Possibly preferring to remain unclassifiable like Redon, Spilliaert’s letters expose his dislike for the movement. At one point, he even writes about a wish for all of his work to be destroyed: “Symbolism, mysticism, it’s all madness, sickness. I’d like to tear up everything I’ve done so far, destroy it all. Ah! If only I could be rid of my restless, excitable nature, if only life did not have me in its grip, I would have simply gone off somewhere into the countryside and dumbly copied what I saw there, exactly what my eyes saw and with nothing added or taken away. That would be life, that would be truth in art.”

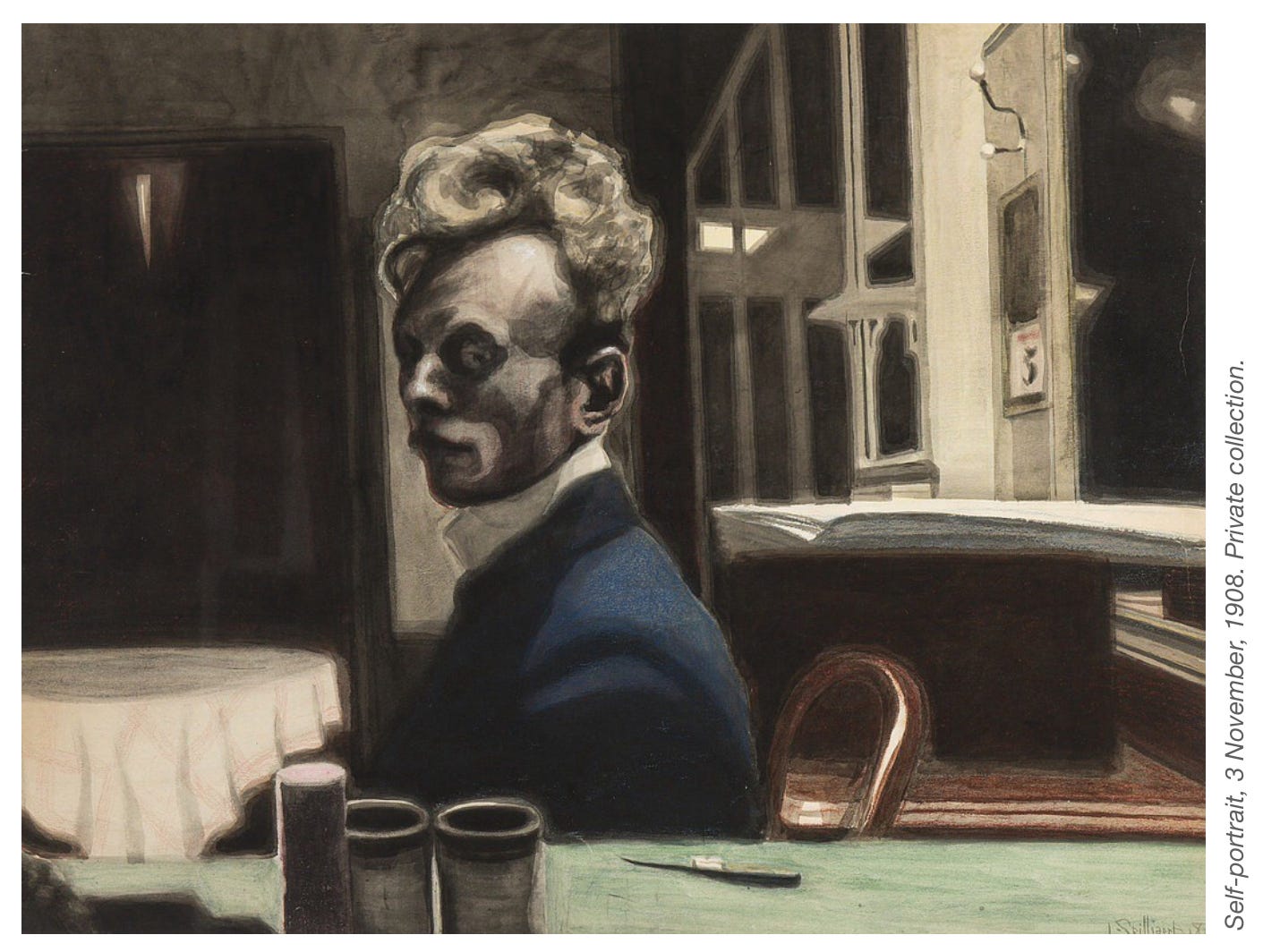

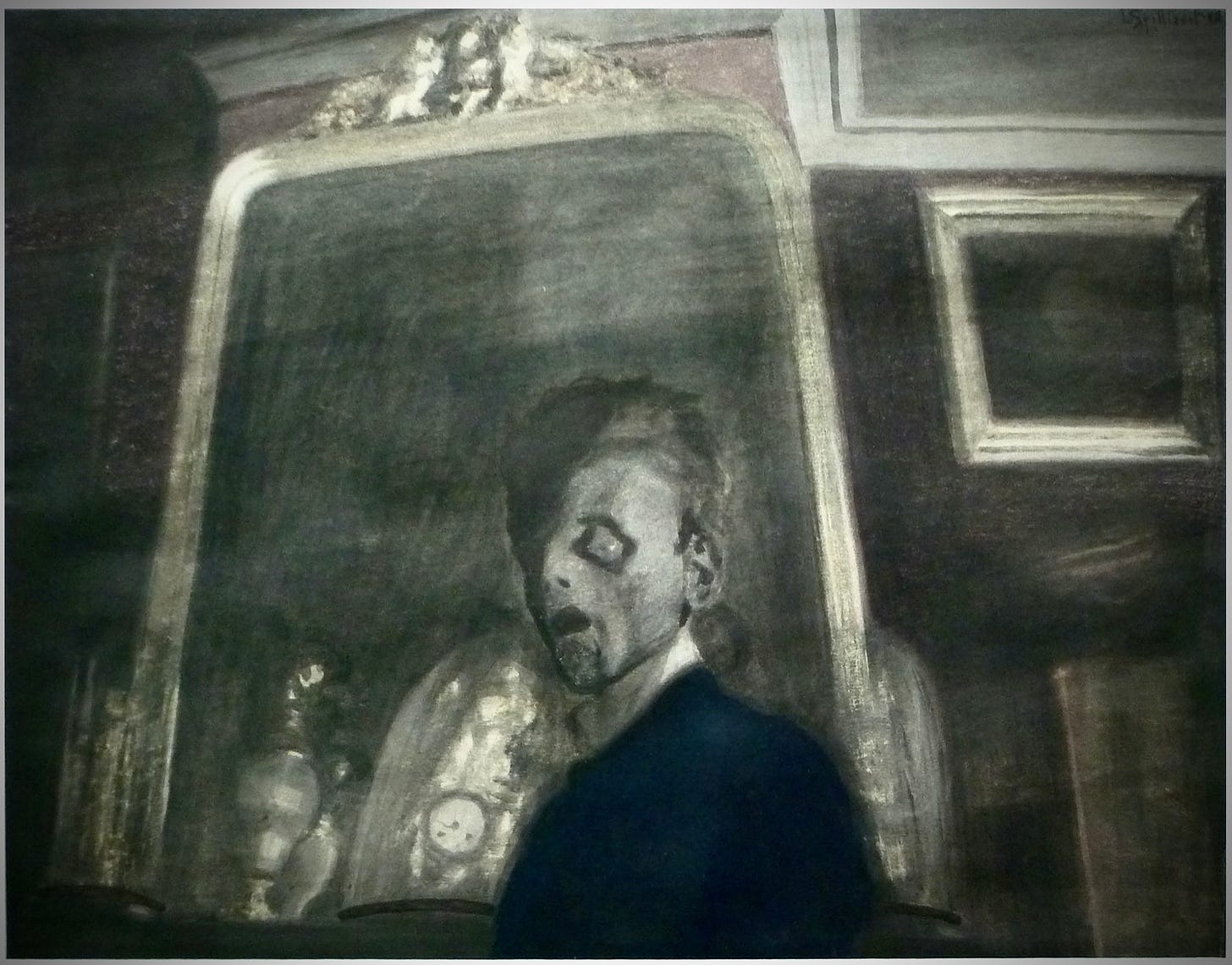

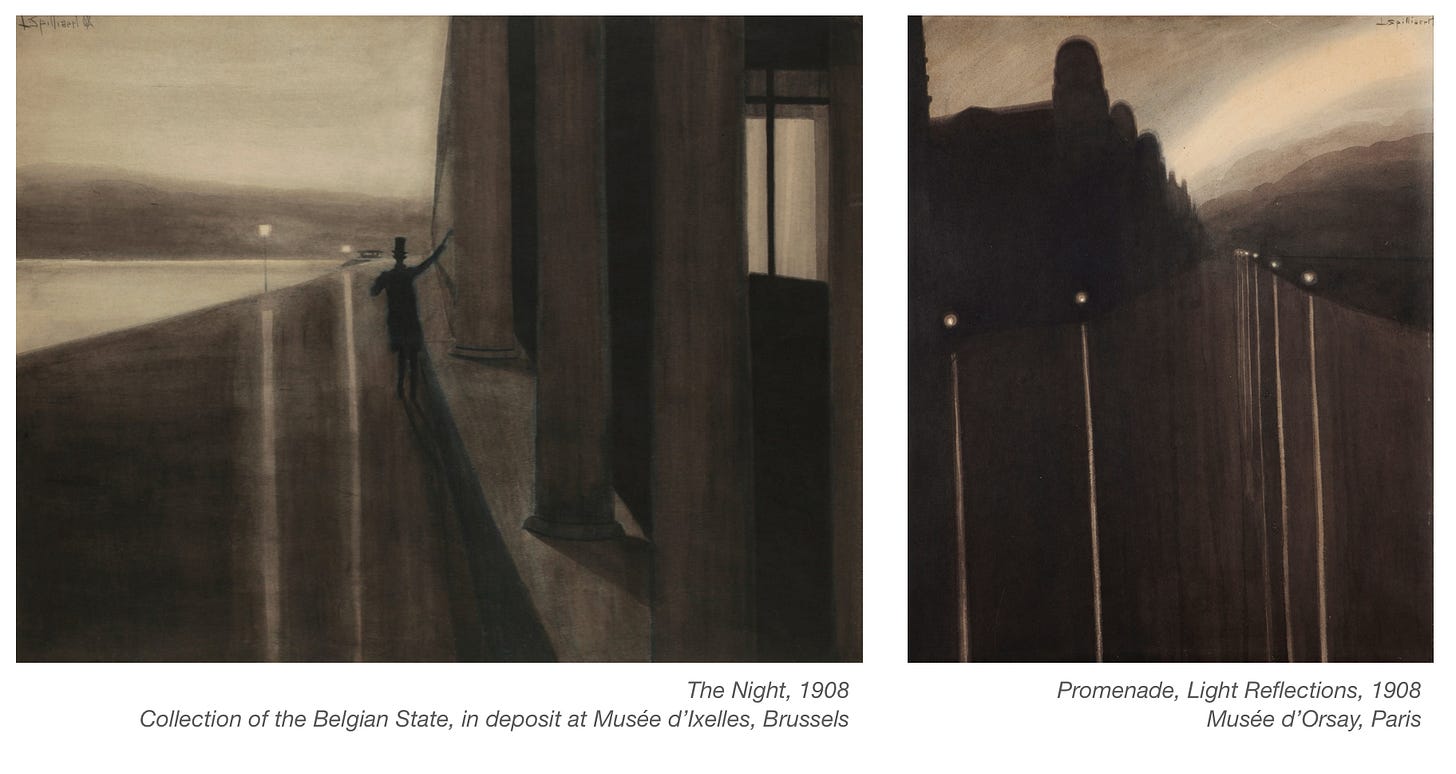

As much as Spilliaert desired to get away, travel, change his place, and so forth, after being away for three years, he would come back to Ostend and say: “I belong here so much and I did not know that I loved the sea to such point. I am living in a real phantasmagoria... All around me, dreams and mirages.” We can see this passion in such beautiful but disturbing scenes as The Night or Promenade, Light Reflections (both painted in 1908). These works show Spilliaert’s masterful, often superimposed layers of the India ink wash applied in shapeless strokes. The dark shades of colour create a muted harmonies sometimes brightened by tiny spots of light. Layers of contrasting shades of watercolour and gouache on paper produce an opaque quality, which creates a depth that pulls our view deeper into the work.

“I wouldn’t have wandered the streets like a sleepless fool. I would never have discovered the beauty of a desolate seafront. I wouldn’t have seen the fishermen setting out and the women waiting for their return. I would never have put the darkness in my soul onto paper.” - Spilliaert

Strange and minimalistic compositions with an ever-elusive vantage point attest to Spilliaert’s extremely stylised perception. His work manifests an entirely different way of looking at a landscape, a completely different element of estrangement and detachment (see Promenade and Casino of Ostend (1909) or his last work Seashore and Dunes (1945) both in private collection). Spilliaert’s works on paper are heavily wrought and large, bigger than normal drawings; intended to hang on a wall just like the oil paintings.

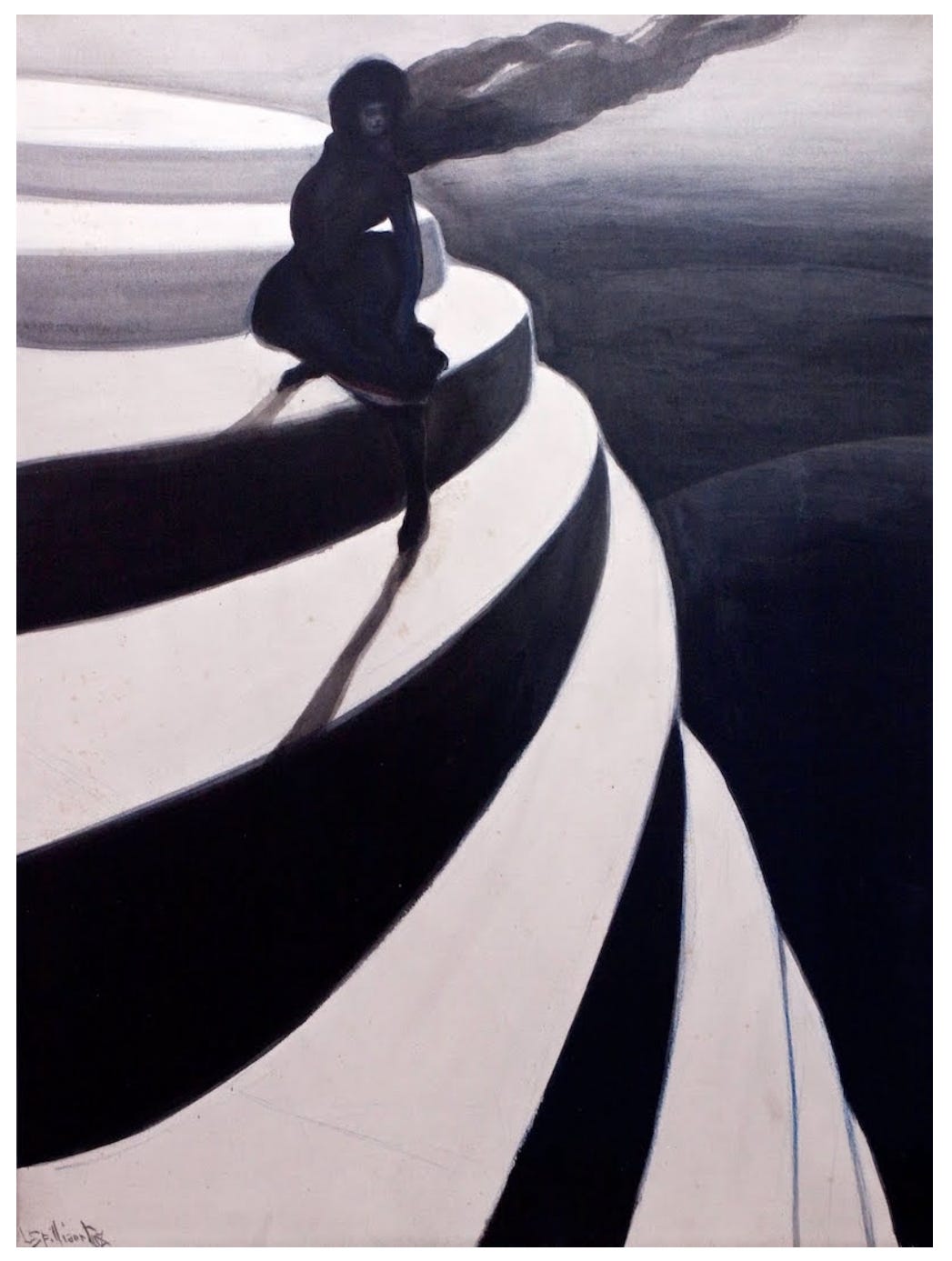

Perhaps the most emblematic work of Spilliaert is the eerie Vertigo. Painted in 1908 with India ink and coloured pencil on paper, it is a painting of a bold contrast that is almost black and white. We see a mysterious female figure draped in black and climbing what looks like a tower of stairs. A strong wind blows from below, making her veil rise like a trail of smoke behind her. The bright light of slightly yellowish shade is falling from above, similar to a beam of a full moon. The figure freezes in a half-turn looking back, as if in a wait of something. We are left wondering - Is it something that she sees? At a closer look, it appears that her eyes turn towards the sky, but we can’t be sure. This painting will not give us any answers.

What it does deliver is a feeling of threat, impeding calamity and suspense in this surreally disturbing composition. The pose that the figure is striking, on such high steps, would give any person vertigo so intense that one would probably fall. This figure, however, appears to exude confidence and absolute control despite this dangerous position. At this point, we might start wondering if the figure is human at all? Or rather a woman-like ghostly apparition - a reoccurring element in many of Spilliaert’s other imaginative works. Images like these make Spilliaert an amazing topographer of an inner-self, everything that has to do with hallucination, fear, and stillness. Stillness draws us closer; it invites our concentration, making us aware of our inner self as we lean in.

Artist of tremendous insight and intensity, Spilliaert’s work is deeply personal. Yet his introspective imagery teaches us the importance of connecting to one’s inner world. His rebellious technique may have displeased the patrons of the arts back in his day, but a 21st-century viewer could feel nothing but respect for Spilliaert’s pure dedication to his artistic expression. The effect of late-night walks in Ostend on Spilliaert is undeniable. His work demonstrates a different form of intellect, another level of deep self-awareness and self-understanding. Plato once asked, “…why should we not calmly and patiently review our own thoughts, and thoroughly examine and see what these appearances in us really are?” In times of rapid change, we are offered a chance to delve into Spilliaert’s still visions. We can find regeneration through prologued contemplation of Spilliaert’s world that exists beyond its creator. ♦

Thank you for reading. If this reflection resonated with you, I’d be delighted if you liked or shared it - and I always welcome your thoughts in the comments. You can also become a member or wander through The Reflective Eye Anthology to revisit earlier meditations.

If you enjoyed this piece on Spilliaert and his art piqued your curiosity, please consider reading a longer article I wrote about him, available here:

Until next time, with warmth & gratitude -